Unbuilt Works - The existing Dickinson College Kline Center

Spillman Farmer Architects’ proposal takes advantage of these features, while striving to introduce more transparency and connectivity as well as making the building’s sustainability evident.

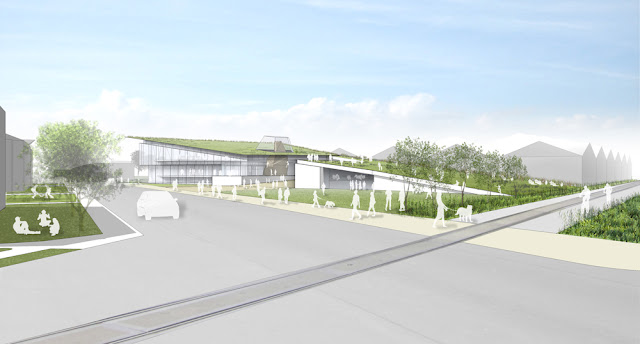

DYNAMIC CAMPUS GATEWAY

The new three-level addition transforms the Kline Center Cherry Street and south to High Street and integrated with the existing topography. The north “wing” features regulation-sized squash courts at the lower level with viewing areas at the main level. The south “wing” features strength training and multipurpose studios at the lower level; juice bar and “see and be seen” gathering spaces and main entrance on the main level; and cardio areas on the upper/mezzanine level.

The south façade of the building, along High Street, features a new landscape intervention of a living green wall, a visually delicate structure anchored by masonry monoliths that together draw one’s gaze along Kline Center

TRANSPARENCY & CONNECTIVITY

The addition is carefully integrated with the existing main entrance and the existing central corridor to achieve a direct and clear entry sequence. The existing corridor is extended through the new addition at the main level to create a central spine activated by program elements with access to the pool and basketball courts. Glass curtain walls and skylights bring natural daylight into the building and introduce dramatic transparency throughout, strengthening connectivity: the physical and visual connections inside and out, and among the different spaces within the facility.

This transparency provides passersby with dynamic views into the building and gives occupants views out, making the facility more inviting and the user’s experience more enjoyable. For the staff of the facility, this interior connectivity allows each activity area to be monitored from a central reception or control desk, increasing safety and security.

You will note that this concept proposes removing the earlier health and fitness center addition that currently does not contribute to the quality of the campus and creating green space on the North along Cherry Street . This move also has the advantage of extending the campus quadrangle outlined in the College’s Master Plan and better connecting both the Kline Center

SUSTAINABILITY

Sustainable features have been purposefully emphasized here. Most visible perhaps is the statement-making green roof envisioned for the facility. Another element is the addition’s internal natural ventilation system, inspired by Zimbabwean termite mounds, that is integrated with the facility’s climbing wall.

Termites in Zimbabwe

In a bit of biomimicry, the new addition features its own “termite mound” structure – the fitness center’s climbing wall, which extends from the lower level to the ceiling and beyond, penetrating the roof. Outside air that is drawn in is either warmed or cooled. It is then vented into the building’s floors and offices before exiting via the termite mound/climbing wall. Thus a dramatic sustainable feature is not only made visible but also useful. And imagine the campus views climbers are rewarded with when they reach the upper holds of the climbing wall!

This design concept also incorporates innovative stormwater management. Currently, stormwater from the Kline Center Kline Center

No comments:

Post a Comment